Why Not All Companies Want Your Ideas

By Nadia Carlsten | On October 15, 2015

A recent article in the LA times tells the story of a long time AT&T customer who sent two ideas to the CEO on how to improve customer experience, only to be answered by the legal department asking him not to contact the company with suggestions ever again. The reaction so far has largely focused on the “bad business” aspect of not valuing customer input, and not too surprisingly, placing the blame on “tone-deaf” policies of the legal department.

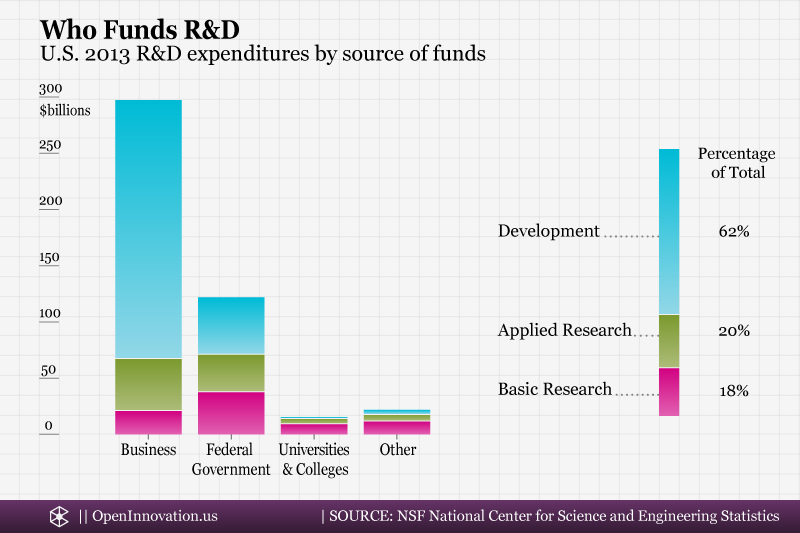

Perhaps this story has been upsetting to people precisely because so many companies have adopted open innovation approaches in dealing with customers. With big brands like Starbucks, Coca Cola, and IBM actively seeking ideas from the public through ideation campaigns and crowdsourcing initiatives, it would seem at first glance that AT&T’s policy is out of touch. Even within the IT industry, leading firms have been known to look outside their walls for new ideas. Nokia for example has a program called “Invent with Nokia” that not only welcomes ideas from the public at large, but incentivizes them with financial rewards.

There is, however, a very good reason why accepting external ideas is a legitimate concern for companies: they are worried about IP contamination.

Whether they are using it to exclude others from the market or exploiting it through other strategies, most companies recognize that their intellectual property is valuable and needs to be protected. IP contamination, or the possibility of creating uncertainty around the ownership of this IP, could prove very costly and open the door to endless legal disputes. Imagine a company develops an idea and implements it successfully. Someone that had submitted a similar idea to the company claims that his idea was used and demands compensation. If the company did in fact interact with external submissions, what keeps the submitter from reasonably believing his idea was improperly used? How does the company prove that it came up with the idea independently, or that it was already in active development? This scenario illustrates the risk, particularly for companies that have ongoing R&D activities. By accepting external ideas without safeguards to protect itself, the company could jeopardize its own internal development pipeline.

AT&T alluded to this very concern in their response. The LA Times article quotes a spokesperson who explains that “in the past, we’ve had customers send us unsolicited ideas and then threaten to take legal action, claiming we stole their ideas”. No wonder then that the company established a policy regarding external ideas. In fact, AT&T is far from alone in this, and most companies make it a point to state on their websites that they will not accept unsolicited ideas. Zynga’s policy for example states that it “does not allow us to accept or consider any unsolicited ideas, suggestions, proposals, comments or materials (“Submissions”). The purpose of this policy is to avoid potential misunderstandings when Zynga’s products, services or features might appear to be similar or identical to ideas submitted to Zynga.” A quick search revealed similar policies for Logitech , Krispe Kreme, and even NBA teams!

But then how to explain those companies who maintain highly visible efforts to reach out and include customers and inventors in their innovation process? My take on it is that the rewards of Open Innovation are too great to ignore new sources of ideas. Just because companies don’t want unsolicited ideas doesn’t mean they can’t innovate with their customers. The key is to minimize the risk of IP contamination through a carefully controlled process. Some strategies that companies can use include:

- Only accepting ideas that are already protected, such as by asking for a patent or patent application.

- Clarifying expectations through legal notices, for example by stressing that only non-confidential ideas are expected and that there is no expectation of confidentiality for the submission.

- Using a portal that manages the process to minimize internal exposure to external submission, for example by controlling who can see external ideas.

- Using an intermediary to collect and review external submission to shield the company from exposure.

For open innovation managers, balancing “openness” and legal issues is a daily struggle. Sometimes the perception of “openness” matters too. But good IP contamination safeguards are a good thing, for companies and submitters alike.