Monetizing Underutilized Patents through Licensing

By Nadia Carlsten | On January 18, 2016

The predominant way that companies extract value from their patents is through the sales of products that include technologies covered by one or multiple patents. Under this paradigm, companies use patenting mostly as a defensive tool that enables them to exercise market power by preventing imitation and suppressing competition. Having a proprietary technology can certainly help secure marketplace advantage, increase profit margins, and create barriers to entry for competitors, so it’s not surprising that companies are often most attracted to the monopolistic position afforded by a patent.

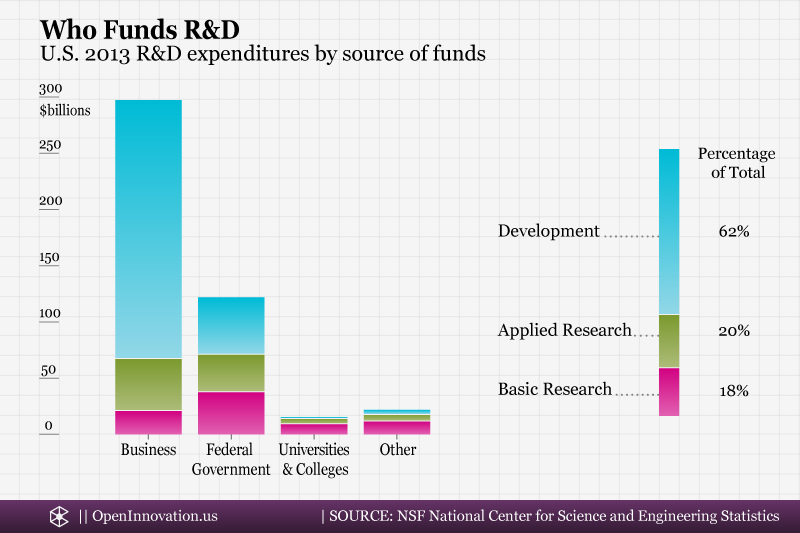

Most companies, however, own patents that are beyond those necessary to protect their products, and which do not provide any obvious value to the company. This can happen as a result of business decisions not to enter certain markets, or through changes in product roadmaps after the patents have already obtained. Likewise, companies that perform research and development activities are a likely setting for new inventions, many of them byproducts of the R&D process and not necessarily related to the original objectives. Combined with a “patent everything” mindset or policy, these companies can find themselves with patents that fall well outside the scope of their expertise.

Since patent maintenance costs are not trivial, especially for global companies and those with large portfolios, companies have to manage these non-core patents.

First, the company has to identify those patents that it does not have the resources to utilize, either because of a lack of expertise or capabilities, or because it does not have the right business model to properly exploit the patent. Second, the company has to decide on a strategy for those patents. For example, many companies keep patents for products that they’ve decided not to pursue, in case they change their mind down the road. Other patents can have strategic value by blocking competitors from a technology area, even if the company has no intention to practice it itself.

An especially attractive way for companies to profit from non-core patents is through licensing. With the success of companies like IBM and Texas Instruments making billions in revenues from licensing IP portfolios, patent licensing as a monetization strategy is gaining a lot of interest from company executives. While the concern of valuable company IP ending up in the wrong hands is still present for some, desires to cut maintenance costs and pressure to show a financial return on investment on R&D activities are reasons companies look for new ways to extract value from underutilized patents, and licensing is a great way to do that.

A license is a grant of permission, which is necessary because patent protection grants exclusive rights to inventors for a finite amount of time. During the life of the patent, no one can exercise the patent holder’s exclusive rights to “make, use, sell or offer to sell, distribute, or import things that practice the patented invention.” The license is a way for a company to acquire the rights to a patent owned by another entity, therefore obtaining “freedom to operate”. As a result, the licensee will be able to practice a method, or sell a product covered by the patent being licensed. Payments can be structured in many ways, but commonly consist of an upfront fee in addition to royalties, which are recurring payments usually based on sales.

Letting another company utilize your patent is not an all or nothing proposition. There are multiple ways to transfer patent rights, and different types of licenses that companies can enter into:

- Non-exclusive licenses grant rights to the patent to a licensee, while at the same time allowing the patent holder to enter into multiple other licenses of the same rights with other parties. The advantage of non-exclusive licenses for the patent holder is the ability to have several license agreements for the same patent, thereby creating multiple sources of income.

- A sole license is used when the patent holder reserves full rights to exploit its own patent for itself, while at the same time licensing the patent rights to one other entity.

- An exclusive license is used to transfer the rights from the patent owner to one party exclusively, so that only the licensee can exploit the patent rights. Patent owners can generally extract higher payments for exclusive licenses. For a licensee who has to make further investments to fully exploit the patent licensed, they are more attractive, since it will not have to compete with others for the same rights.

- An exclusive license of “all substantial rights” is a distinction for an exclusive license that includes additional legal rights, including the right of the licensee to assert the licensed patent against third parties. A licensee does not usually have standing to sue for infringement without the patent-owner joining the suit, but the licensing agreement can be drafted to include these rights. 1

- A patent assignment transfers the patent owner’s legal title and all rights to the patents to the assignee. This is a different from any type of license, where the patent holder still retains ownership while transferring some or all of the rights, and the choice between assigning a patent rather than licensing it has important legal and tax implications. In the context of monetization, these patent “sales” are most often encountered when companies go bankrupt or auction off patent portfolios for lines of business they are exiting.

Through the license grant, the company can further control how much of its patent rights to transfer. Patents are different from copyrights in that they are not infinitely divisible: patent owners can’t license different claims from the same patent to different parties. However, it is possible to maximize the number of ways to profit from the same patent by defining the scope of the rights being transferred precisely. Two strategies to consider:

Define field of use restrictions for each licensee.

This limits how each licensee can use the patent rights based on specified applications or implementations of the patented technology. In biotech for example, it is common to license a single compound under multiple licenses, each granting rights for a narrow field corresponding to a specific disease.Grant each of the patent’s exclusive rights to different parties.

For example, for a patent covering a technology that you don’t want to commercialize yourself, it’s possible to grant one company the exclusive right to manufacture it, while granting another the exclusive right to sell it. As the patent owner, you receive license payments from both while optimizing the path to commercialization.

Licensing is an integral part of any good IP strategy. In many cases, it’s possible to monetize unused patents that would otherwise sit on the shelf, and there is a myriad of ways to structure licensing agreements to maximize revenue generated from patent licenses. In addition to financial motivations, there are strategic reasons why you should consider licensing your patents, including cross-licensing to reduce exposure to costly patent infringement litigation, and licensing for open innovation, which I will discuss in another article. Whatever the goal is, using licensing as part of your IP strategy means that you don’t have to practice a patent to benefit from it.

Notes

- For examples of legal consequences related to the transfer of substantial rights during licensing, see Luminara Worldwide, LLC v. Liown Electronics Co. and Keranos, LLC v. Silicon Storage Tech., Inc. ^