Cutting Edge Technology or Not, Theranos Could Still Be Disruptive

By Nadia Carlsten | On November 01, 2015

In many ways, the Theranos story illustrates how the hype that often surrounds Silicon Valley’s most promising startups is a double-edged sword. A “unicorn” with a $9 billion valuation, the blood-testing startup has gone from being the subject of glowing profiles to facing an onslaught of unflattering reports and speculation about its capabilities in a matter of weeks. Ever since the Wall Street Journal raised questions about the reliability of the technology behind its tests,1 Theranos has had to play defense against ever increasing scrutiny. For many, the startup has become the latest example of investors too willing to “throw money at a good story”.

The coverage of Theranos however, and of technology startups in general, reveals serious misconceptions about what disruptive innovation actually is. “Faster, cheaper, better. An innovation that accomplishes those three things has the potential to disrupt an industry”. So begins one of the articles2 that describes Theranos and its technology. In fact, it’s hard to find a single article that doesn’t mention the startup’s potential to disrupt the clinical testing market in the same breath as it describes its innovative technology.

In reality, disruptive technologies are never “faster, cheaper, better”. Clay Christensen’s extensive research in this area shows that unlike sustaining technologies, which maintain the rate of improvement for attributes that customers already value, disruptive technologies often perform far worse, and would not be considered “better” by the mainstream customers. Rather, disruptive technologies offer different performance attributes that improve rapidly, enabling the new technology to “invade the established market”. Most disruptive technologies never even outperform the established technology in terms of technical performance, but eventually they meet the needs of the established market.

Nor is disruptive technology synonymous with cutting edge technology. When the WSJ brought to light that most of the testing performed by Theranos is done by conventional methods rather than its own technology, the allegation was considered quite damning for a startup seeking to innovate how testing of clinical samples is done. Fortune magazine declared: “The company “does the vast majority of its tests with traditional machines bought from companies like Siemens AG.” Obviously, that doesn’t sound very disruptive.”3

To be sure, even the core science behind what Theranos is trying to accomplish is not as new as the original fawning reports about it would make it seem. The startup hopes to use microliter sized blood samples to run diagnostic tests that would generally require 100 to 1000 orders of magnitude larger samples using traditional methods. Microfluidics has been an active area of research for at least three decades, and there are several other startups focused on using lab-on-chip devices to run analytical tests of biological samples. How Theranos manages to get accurate and reliable results on a scale where other have not remains a trade secret, something that has caused skepticism in the scientific community.

Regardless of whether the technology itself turns out to be a breakthrough, however, it’s how Theranos will utilize it to satisfy the needs demanded by the market that matters most. Diagnostic testing is a $75 billion industry, and tests ordered by doctors are estimated to guide 70% of medical decisions.4 Most of the innovation is happening behind the scenes, in the form of better analyzers and more reliable analytical processes, invisible to the customers. It’s also a market vulnerable to disruption: because existing performance demands have been satisfied, new dimensions of performance can emerge and take on more importance for customers. Theranos has an opportunity to compete on new performance attributes such as convenience, or painlessness of the process.

Whether or not Theranos does indeed disrupt the industry largely depends on how it decides to position itself in the near future. What market the startup decides to target will have larger implications for revenues than which technology it uses. True disruptive technologies offer a set of performance attributes that are often valued only in new markets. For Theranos, this could mean the emergence of a new market for frequent testing where accuracy and other current performance attributes are not as important. Capturing that new market would be an important step before the company can compete in the established market. Fortune3 notes changes in Theranos’s marketing from an emphasis on its micro-vials to highlighting a “better experience”, which could indicate that the startup is trying to reposition itself.

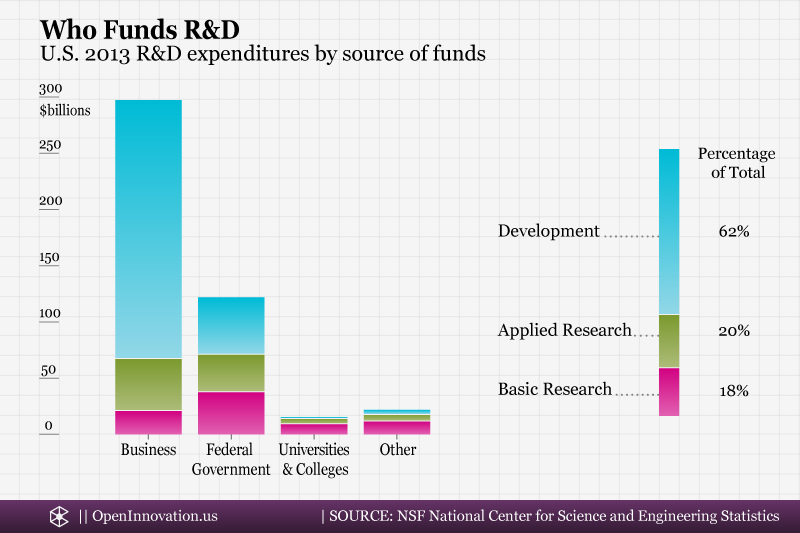

The potential for disruption will also depend on what business model Theranos adopts. The diagnostic testing business requires many capabilities that will place the young startup in unfamiliar territory, from the logistics of sample collection, to billing, and regulatory compliance. The focus on Theranos’s new technology has meant that few have questioned the company’s ability to scale up if it is to emulate a traditional laboratory testing business model. In fact, the services model that the company seems to be pursuing currently might not even be the best way to compete. Testing of microfluidic samples has so far been limited by a lack of commercially available and reliable miniaturized lab systems to perform the analysis. Theranos could arguably capture more value by selling the analyzers that make its results possible, or even better, by using it as a technology platform to stake its place in the industry like Millenium Pharmaceuticals did in the 1990s.

It’s easy to get caught up in the hype surrounding a new technology, or to give in to the impulse to dismiss it because it’s not “better” after all. Andy Grove summed it up best:

“Disruptive Technology is a misnomer. What it really is, is trivial technology that screws up your business model”

Andy Grove

Spotting true disruptive technologies can be hard, but it’s important for anyone who has to make decisions about new ventures. The newest, flashiest technology will seldom be disruptive. A well-positioned technology that creates and captures value through a clever business model might very well be.

Notes

- Carreyrou, John. “Hot Startup Theranos Has Struggled With Its Blood-Test Technology.” Wall Street Journal 16 Oct. 2015. ^

- Loria, Kevin. “Scientists are skeptical about the secret blood test that has made Elizabeth Holmes a billionaire.” Business Insider 25 Apr. 2015. ^

- Parloff, Roger. “Are the Wall Street Journal’s allegations about Theranos true?” Fortune 15 Oct. 2015. ^

- Parloff, Roger. “This CEO is out for blood” Fortune 12 Jun. 2014. ^